SIOUX FALLS, S.D. — The auditorium at Southeast Technical College was brimming with South Dakotans, many voicing their opposition to Summit Carbon Solutions’ controversial carbon dioxide pipeline proposal. The significant turnout underscored the local concern on Wednesday evening as the state’s Public Utilities Commission reconvened to deliberate on the project’s permit amidst widespread resistance.

Commissioner Gary Hanson opened the three-hour session with a note, stating, “We know this is an incredibly important issue to you,” addressing the assembly. “We are here today to learn and listen, and we appreciate each of you being with us today to give us your input.”

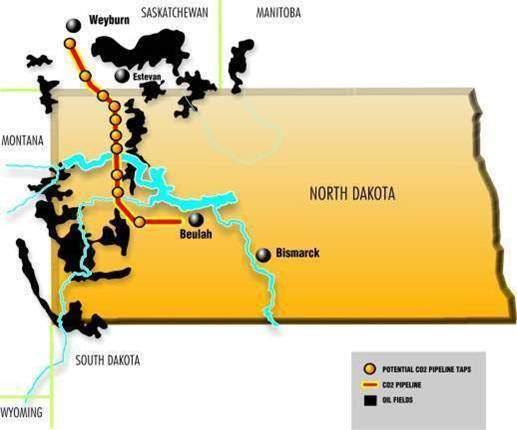

The proposed venture by the Iowa-based Summit Carbon Solutions involves a massive 2,500-mile, $9 billion pipeline designed to capture carbon dioxide emissions from 57 ethanol plants scattered across five states, including the eastern stretches of South Dakota. This captured CO2 would then be transported to North Dakota for underground storage.

The project is poised to leverage federal tax incentives that encourage the reduction of carbon emissions, raising questions about the motivations behind the project, particularly its environmental and economic implications.

South Dakota’s pivotal role in this project has sparked extensive debate. Despite having already secured necessary storage permits in North Dakota and route validations from several neighboring states, Summit’s efforts were thwarted in 2023 when the Public Utilities Commission denied their initial permit application due to route conflicts with local ordinances. The commission’s replay of last year’s decision hinges on similar concerns this time around.

The Sioux Falls gathering was crucial, bringing together residents from counties like Minnehaha, Lincoln, Turner, and Union—areas directly affected by the pipeline route. A previous session had already been held in Mitchell, further underscoring the regional importance and urgency of this discussion.

Gary Hanson

Public apprehension was palpable, as most attendees expressed stark objections to the pipeline plans, highlighting safety risks and potential damage to farmland. The vocal crowd made their stance clear with frequent rounds of applause following each opponent’s argument.

Among the disputants was Betty Strom, whose farm falls within the prospective pipeline corridor. She characterized it as a “forever hazard across my land.” Candidly, Strom remarked, “Summit is in it for the tax credits. They don’t care about property rights, safety, the damage to property, its value, or the long-term consequences. Please deny this permit again.”

Summit representatives at the hearing defended the selected route, stressing the comprehensive adherence to safety regulations and standards. They outlined that the project promises $1.9 billion in capital expenditure within South Dakota, with projections of generating 3,000 construction jobs and sustaining 260 permanent jobs annually post-construction.

From an economic standpoint, supporters argue potential benefits for the state. Al Giese, an Iowa farmer and board member for the Iowa Renewable Fuels Association, highlighted the necessity of carbon sequestration for the agricultural sector’s future, declaring, “The carbon sequestration train, locally and nationally, has left the station. Yes, it is a South Dakota issue. It is a Midwestern issue. But we must move forward with sequestering carbon not only for the vitality of the ag sector but for all the economies in the Midwestern states.”

However, significant legal and public policy challenges lie ahead for the project. The South Dakota Supreme Court’s recent ruling demands stronger justification from Summit before allowing the use of eminent domain—a key leverage tool Summit seeks under the common carrier designation, essential for land acquisition.

Moreover, a legislative push gains momentum as some state lawmakers propose banning the use of eminent domain for such projects altogether, reflecting a growing sentiment against large-scale pipelines impinging on private land rights without solid public benefit justification.

The narrative of this pipeline journey is emblematic of the larger economic and environmental crossroads faced by South Dakota. As stakeholders await the next round of public meetings in De Smet and Watertown, then Aberdeen and Redfield, the conversations underscore the complex interplay between technological advancement, public policy, and grassroots resistance. These gatherings offer a crucial platform for citizens to influence decisions central to the state’s landscape, both socioeconomic and literal.

For further inquiries, reach out to Editor Seth Tupper: [email protected]