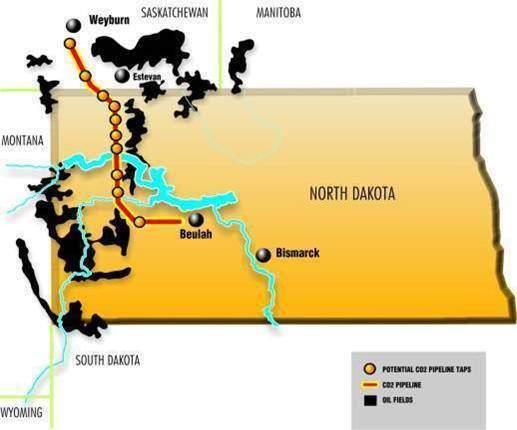

Summit Carbon Solutions, an Iowa-based company, is at the heart of a contentious debate in South Dakota regarding its proposed $9 billion carbon dioxide pipeline project. The company aims to capture emissions from 57 ethanol plants and store them underground in North Dakota, effectively reducing carbon emissions in the region. However, as the Public Utilities Commission (PUC) deliberates on approving the company’s permit application, questions of conflict of interest have surfaced, involving high-profile state officials.

The controversy pivots around Kristie Fiegen, a seasoned South Dakota politician and current member of the South Dakota Public Utilities Commission. With a strong background in economics and agriculture, Fiegen has served on the commission since 2011, playing a crucial role in evaluating infrastructure projects that affect the state [Email the commission].

Kristie Fiegen

Summit has formally requested Fiegen to recuse herself from the project’s permit application process due to a potential conflict of interest. This request is grounded in the fact that the pipeline’s proposed route crosses land owned by Fiegen’s sister-in-law, Jean Fiegen-Ordal, and her husband, Jeffrey Ordal. The Ordals’ land is part of the Jeffrey A. Ordal Living Trust, which owns parcels in both Minnehaha and McCook Counties. Summit has invested $175,000 in easements and crop damages for these properties, intensifying scrutiny over Fiegen’s impartiality.

In 2023, the PUC, which includes Commissioner Fiegen, rejected Summit’s initial pipeline application. The decision was influenced by route conflicts with county ordinances dictating minimum pipeline distances from existing features. During that period, Kristie Fiegen recused herself following similar conflict of interest concerns, paving the way for South Dakota State Treasurer Josh Haeder to step in. Summit posits that this situation remains unchanged, pressing for Fiegen’s recusal yet again.

In an emailed statement, Summit cautioned, “Because your family has a direct interest in the approval or denial of the permit, and because you previously recused yourself in two dockets based on the same facts, a court almost certainly would find it inappropriate for you to participate in this docket.” They warn that her continued engagement could spark litigation, appealing the commission’s eventual decision, or delaying the permitting process, potentially stalling the project.

The company’s new letter has attracted criticism from Brian Jorde, an attorney with the Domina Law Group in Omaha, Nebraska. Jorde, who specializes in cases involving land use and environmental law, fiercely defended Fiegen, saying, “From my viewpoint she never had a conflict that rises to the level of recusal and certainly doesn’t now.” Jorde argues that the familial link through marriage doesn’t equate to a direct conflict of interest.

Josh Haeder

The unfolding scenario places spotlight on South Dakota, a state deeply rooted in agriculture with a vested interest in infrastructure that supports economic development. The pipeline promises alignment with federal tax credits aimed at curbing carbon emissions, which has sparked a technological boom in the Midwest. Yet, local communities remain torn, balancing environmental stewardship with economic opportunity.

South Dakota’s role in the energy sector is shifting, and the involvement of elected officials like Kristie Fiegen is under stricter scrutiny. As a responsible steward of public trust, Fiegen’s educational background from South Dakota State University and her MBA from the University of South Dakota highlight her preparedness for such governance challenges. Her ties to local communities through organizations such as Rotary and United Way reflect her longstanding commitment to public service.

Starting January 15, the PUC will host public input meetings in eastern South Dakota cities near the pipeline route, opening the floor for community voices. Public participation remains a pivotal element, especially when the proposed infrastructure embarks on altering South Dakota’s economic landscape.

Brian Jorde

While Summit has secured necessary permits in North Dakota, Iowa, and Minnesota, the absence of a state permitting process in Nebraska underscores the complexity of navigating multi-state infrastructure projects — a trademark challenge in carbon capture initiatives. The looming threat of litigation and the possibility of future amendments to route proposals add layers of uncertainty, yet also potential for innovation and collaboration.

The carbon pipeline debate in South Dakota encapsulates a larger narrative about energy, responsibility, and the future of ecological stewardship. This dialogue cuts across community concerns and state ambitions, converging on the principle that sustainable development must reckon with all voices at the table. Commissioner Fiegen, backed by a history of public service, is at the center of this critical juncture, where her decisions may well steer the trajectory of South Dakota’s environmental legacy.

In conclusion, as South Dakota’s communities engage with stakeholders like Summit Carbon Solutions, they’re participating in a broader discourse on aligning economic development with environmental consciousness — a pressing challenge in contemporary governance.